From Leibniz to Google:

Five Paradigms of Artificial Intelligence Instructor: David Auerbach Date & Time: Saturdays, December 7, 14, January 4, 11, 18, 25, February 8, 15 11 AM - 1:30 PM ET

DESCRIPTION What does it take to create intelligence–and to recognize it? These are the two concerns that have animated the field of artificial intelligence over the last 80 years. This Seminar situates the AI field in the larger traditions of philosophy in order to make explicit the frequently unrecognized foundations of AI–as well as how those foundations have shifted several times alongside AI’s fortunes. AI always brings with it many post-Kantian questions of epistemology, ontology, subjectivity, and phenomenology, but these dependencies are often left implicit, even as they undergo large paradigm shifts.

This Seminar will examine the transitions between a successive series of paradigms of artificial intelligence, with very approximate periods of dominance: (1) Speculative (to 1940), (2) Cybernetic (1940-1955), (3) Symbolic AI (1955-1985), (4) Subsymbolic AI (1985-2010), and (5) Deep Learning (2010-present). We begin with the prehistory of AI, examining dreams of machine reasoning from Leibniz to La Mettrie to Lovelace and onward. While AI’s most famous definition was given by Alan Turing in his visionary 1950 paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” his functional approach had already been anticipated in the cybernetic research of Norbert Wiener, Warren McCulloch, W. Ross Ashby, William Grey Walter, and Frank Rosenblatt. In conceiving of AI as fundamentally embodied systems in a feedback-driven relationship with their environment, cybernetics is a more radically intersubjective and yet in a battle similar to the analytic vs. continental duel in philosophy, cybernetic-derived approaches lost out in favor of the rationalist Symbolic AI paradigm theorized by Herbert Simon, Alan Newell, Marvin Minsky, and Noam Chomsky, among others. Drawing explicitly from logical positivism and the Vienna Circle (Rudolf Carnap in particular), the Symbolic AI leaders posited AI as a matter of centralized logical symbolic representation–a matter of a disembodied “mind” manipulating representational symbols in order to reason. It was this paradigm, which came to be known as “Good Old-Fashioned AI” or GOFAI, that subsequently took center stage for much of the latter half of the 20th century.

The rationalist symbolic AI (or “GOFAI”) paradigm, and its major exponents including Herbert Simon, Alan Newell, Marvin Minsky, and Noam Chomsky. Rooted in the logical positivism of Rudolf Carnap and the Viennese circle, symbolic AI often goes unrecognized as the most significant attempt to apply logical positivist analysis to reality itself. Its results are the best evidence available for both the strengths and failures of logical positivist, verificationist, and atomistic epistemologies. The rationalist paradigm failed to make good on its promise, leading to the “AI winter” of the 1970s and 1980s. It was then that subsymbolic approaches, hearkening back to cybernetics, began to reappear, with the machine learning and statistical innovations of Rumelhart, Sejnowski, and others. We shall look at the extent to which the subsymbolic approach represented a rejection not just of symbolic AI but of cognitive rationalism itself. By turning its back on the analytic philosophical tradition that had grown out of the Vienna school of logical positivists, AI set the tone for a larger philosophical shift in social discourse: the abandonment of claims to a logical structure first of the mind, and more broadly of the world itself.

Subsymbolic AI achieved far greater prominence when it was combined with technological and corporate developments to produce the Deep Learning boom of the last decade. Only with the enormous computing power provided by Moore’s law, and with the massive data stores accumulated by Google and Facebook, did the subsymbolic approach reveal its true potential. Google’s revealation that it had conquered the game of Go through machine learning, blowing away decades of research, was a stunning monument to the victory of the opaque and inscrutable systems that machine learning had birthed. Philosophically, it is every rationalist’s nightmare: the triumph of the inexplicable over the clear, and that of the probabilistic over the deterministic, obtained through the combination of collected private data and non-symbolic networks. Here Charles Sanders Peirce’s tychism and Georg Simmel’s dynamism will help us understand what these developments mean for the future of human (and machine) subjectivity.

This Seminar will treat AI and its roots in computation and algorithms not as digital artifacts but as human conceptual structures, out of which actual computing is only one manifestation and perhaps not even its most crucial. Influenced by the German philosophical anthropologist Hans Blumenberg, The seminar probes the ways in which the fundamental substrate of human understanding lay in certain “absolute metaphors” such as light, water, fire, and other primitive and omnipresent concepts, adding to the list several more concepts such as number, probability, and data. They do, however, depend on the usage of the same absolute metaphors of number, probability, and data that simultaneously informed developments in computational theory. And in each stage, those absolute metaphors have been necessary tools for understanding the increasing scale of the world and the individual’s seemingly shrinking place within it.

Readings will be drawn from the above-named, as well as histories and treatments of AI by Margaret Boden, Stanislaw Lem, Rom Harre, Pedro Domingos, Juan Roederer, Eden Medina, and others. In addition to Carnap, Peirce, and Simmel, we will consider a number of other philosophers to provide broader context for the issues raised.What is required to create intelligence–and to recognize it? These are the two concerns that have animated the field of artificial intelligence over the last 80 years. This course situates the AI field in the larger traditions of philosophy in order to make explicit the frequently unrecognized foundations of AI–as well as how those foundations have shifted several times alongside AI’s fortunes. AI always brings with it many post-Kantian questions of epistemology, ontology, subjectivity, and phenomenology, but these dependencies are often left implicit, even as they undergo large paradigm shifts.

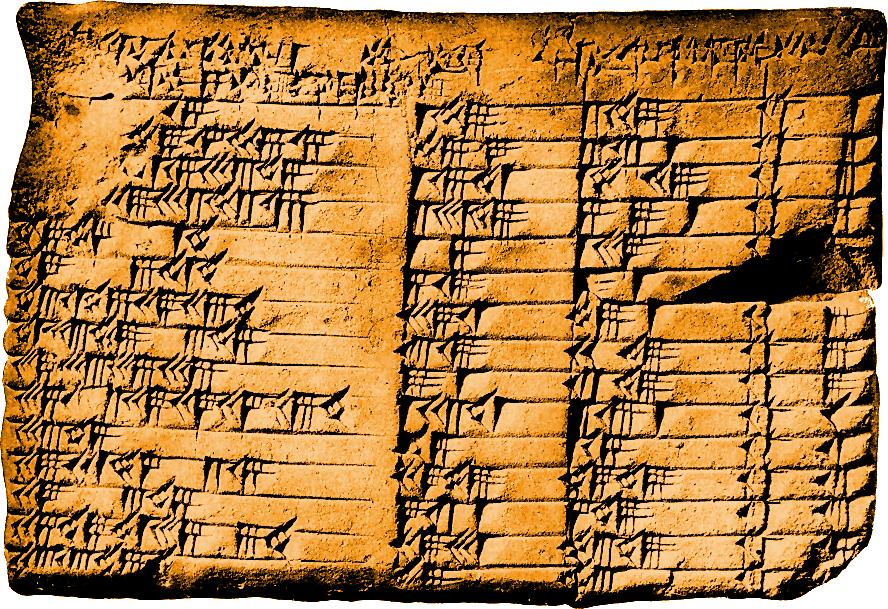

Image: Babylonian tablet listing Pythagorean triples

To see The New Centre Refund Policy CLICK HERE.

To see The New Centre Refund Policy CLICK HERE.